This post aims to be a continuation of an off-topic discussion started in The best approach to learning Rust - #19 by donallen , where it was claimed that Rust's cost-benefit proposition is only worthwhile in a relatively restricted corner of the programming landscape (almost entirely excluding user-space applications, for example), due to the fact that modern hardware is very fast and requires less careful handling from software, whereas the complexity of Rust's efficiency-oriented lifetime and borrowing system leads to reduced programmer productivity which is on its side a very expensive commodity.

In this discussion, it was acknowledged that Rust has more to offer to programmers than a lifetime system. That its highly expressive static typing system improves self-documentation and compile-time error checking, thusly reducing the need for the tedious manual debugging that is the norm in dynamically typed programming languages, for example. Or that its ownership and borrow mechanism greatly simplifies the task of leveraging multi-core hardware parallelism. Which led to a shift of the discussion towards how Rust compares to other modern statically typed programming languages, such as Go or Haskell, aiming to simplify the programming of such hardware.

A first counter-argument that was given was that one underlying assumption of this discussion, while not inaccurate, is quite misleading. While it is true that computer hardware has, for several decades, quickly increased in performance, leading to a shift in the balance between expending programmer effort in software optimization on one side, and prioritizing manpower savings through increased hardware expenditures on the other side, this statement has stopped being accurate in the middle of the 2000s, when the race towards faster CPU clocks, memory bus performance, and instruction-level parallelism came to a near complete halt.

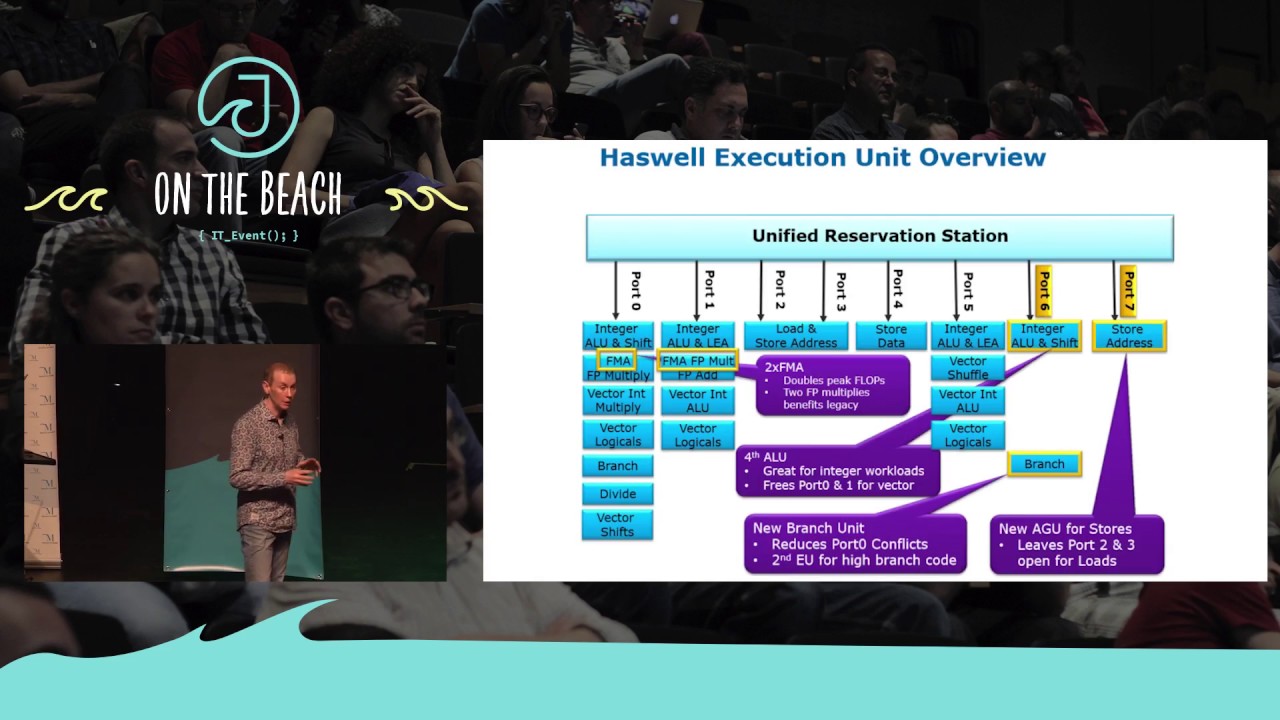

Modern computer hardware only increases in performance through mechanism which are, to a large extent, not transparent to the programmer, and require explicit support on the software side. These include:

- Multi-core parallelism (and hardware multi-threading in general), which is the best-known one.

- Vectorization, which increases the CPU throughput of a program per instruction, but can only be automatically carried out by compilers in specific cases (when memory regions are properly aligned and not mutably aliased, and control flow is not too complex, for example).

- Increasingly deep and complex memory hierarchies, whose fastest layers are so starved for space that they are in practice as difficult to fit in as older-generation computers, with the added complexity of new cache trashing phenomena such as false sharing.

- Specialized hardware accelerators, such as GPUs or FPGAs, whose programming model is fundamentally different from CPUs in the sense that they are much less forgiving of complex code, sophisticated control flow, and high memory footprints.

In effect, computers are arguably more difficult to program efficiently today than they have ever been, and acknowledging this complexity by giving programmers tools to fight it entails a lot more than just multi-core support.

A second point that was raised is that while it is true that programmers can waste a lot of precious time chasing imaginary performance requirements, they can just as well waste everyone else's time and CPU power by failing to properly account for the performance requirements that they actually have. Examples of practical software performance concerns that were invoked were the electrical power consumption of data centers, monotonically degrading performance of many productivity-oriented desktop applications, and tragically bad battery life of energy-constrained mobile devices.

From this point of view, it was claimed that there is actually a real need for software performance in many applications, both user-land and elsewhere, and that Rust can be a productivity boon for programmers having efficiency needs as it is ahead of available alternatives as far as the "highly efficient, but still productive" compromise is concerned.

To both of these points, it was replied that Haskell is a better solution than Rust, due to its strong support of multi-core parallelism, which is what I am going to reply to now.

I don't think that Haskell would be a good solution to the software efficiency crisis that we are traversing (irrespective of the many other merits of this language), because it only focuses on some aspects of modern hardware efficiency at the expense of others:

- Multi-core is only one part of the hardware equation. If your take on leveraging it involves lots of memory copies (originating from a focus on immutability and recursion) and an indirection-rich data model, you are likely to lose in memory performance what you gain in parallelism elsewhere. This is why benchmark-winning Haskell code is usually very far from one would consider idiomatic or clean code in this language.

- While vectorizing Haskell code is not impossible, the implementation strategy of this language does not lend itself very well to it. Lazy evaluation leads to conditionals-heavy code, which most SIMD architectures are enemies of, and indirection-heavy data structures such as lists are all but impossible to write efficient vector code for. Again, Haskell code which vectorizes well will be very far from idiomatic use of the language, making it difficult to write. Contrast with libraries like faster in Rust, which leverages the language's support for efficient high-level abstractions in order to make SIMD code very natural to write.

- Idiomatic use of garbage collection naturally leads to an indirection-heavy data model which trashes CPU caches by having them load plenty of useless data only to leverage a small pointer out of it. Any programming language which relies heavily on it as a native abstraction will be in trouble when trying to make the most of the limited capabilities of modern CPU's highly stressed memory subsystems. This point also applies to Go or Java, for example.

- All the previous discussions become even more salient when targeting hardware accelerators, such as GPUs or FPGAs, which are becoming increasingly popular in areas such as high-speed finance computations or machine learning. While Rust has not yet made very strong inroads in this area, I expect its "keep the runtime lean and compile down to highly efficient code" approach to shine in this area of computing, and am very excited about projects aiming to compile Rust down to SPIR-V GPU shaders for example.

(@donallen, please drop me a PM if you think that I misrepresented some of your points in this summary, I am ready to improve it if needed).